‘Riches to Rags’

Part III: A California pottery in a chicken coop

The workforce of KTK California in 1942 included John Taylor and Pearl Taylor at left, Hazel and Ray Cliff at right, and E.O. “Dubby” Davidson, center back. Behind them are two of the chicken coops they converted into a pottery.

By FRED MILLER

EAST LIVERPOOL –McKinley’s protective tariffs on pottery were long gone, erased by the free-trade Democrats, but sales also were impacted not only by cheap imports but by new materials, especially glass and aluminum. (Grays, Amazing Ware) As dinnerware sales went cold in the late 1920s, talk of merging potteries heated up.

“Everyone was going to make more money than ever before and not have as much responsibility. Grandfather (Sebring), Homer, my uncles, and all the others could really look forward to nice vacations,” Eileen Taylor Davidson recalled.

When Grandmother Belle Taylor died in 1925, her will had disbursed KT&K company stock to Homer, his sister-in-law Mamie McDonald Taylor and Mamie’s two daughters. Mamie’s brother John McDonald had also received stock. The family split turned into bitter open warfare at a stockholders annual meeting. “. . . The gist of the meeting was Dad (President Homer J. Taylor) was fired and John McDonald would be boss.” (Eileen)

On March 11, 1929, KT&K officers voted to join in the American Chinaware Corporation with seven other Ohio potteries. E.H. Sebring China, Carrolton Pottery, Morgan-Belleek China, National China, Sebring Manufacturing, Smith-Phillips China and Pope-Gosser China. In 1931 American Chinaware declared bankruptcy and the potteries were shuttered. (Grays)

“My trusting father!,” Eileen wrote, “He had always been so generous with Mamie and her two girls, had even given them part of his salary when they had to move into the small house because of John and Belle’s house bring sold to the city. They had never lived in a small house without servants. . .Well, like my father, I have forgiven them. . . I’ll be damned if I let them keep me out of heaven.”

Selling out and heading west

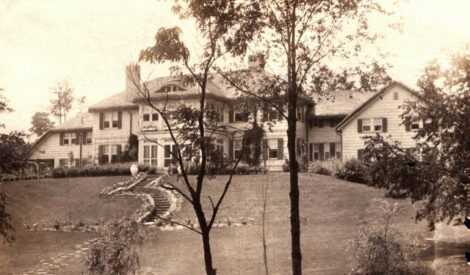

Occupants of the Taylors’ big Park Boulevard house had to learn to cook, clean, and keep up three acres of gardens and lawn because the maids, butler and gardener were let go. Other bankrupt potter owners were taking similar measures. Mortgages were taken out on homes and insurance policies were cashed in. “My grandfather (Sebring) and two of my uncles had succumbed from grief over the failure of the merger and their life savings being swept away,” Eileen Taylor wrote. “Homer and the other former owners were jobless.”

In the summer of 1933 Ray Cliff, who had married Pearl’s sister Hazel Sebring, heard of a struggling pottery in California that might be open to newmanagement. He and Homer took a train for the West Coast July 17 to offer their services and find investors. As Taylor and Cliff family members at home dreamed of “living midst movie stars and palm trees,” each hopeful report from Ray and Homer was dashed in the next letter.

Son John Oliver Taylor met a man called “The Major” who convinced those in East Liverpool of his ties to wealthy investors in California. First-class tickets were bought for him and John to head west unannounced, to surprise Homer and Ray with the positive prospect. The surprise was that The Major was a swindler who disappeared along the way. Arriving alone at Los Angeles, John holed up at a YMCA for three days, ashamed to face his father. (John would turn to drink, never marry, and never find personal success as did his sisters and cousins. Yet he remained within the family circle and labored in the California pottery to the end.)

Pearl and the others left behind, mostly women, were tired of waiting. They decided to buy a car and trailer and rejoin the men in California. With the bank to foreclose on their Park Boulevard home, they tagged furnishings to raise cash for the move. For days bargain-hunters and sightseers trooped through their home. Pearl overheard a conversation in which one snobbish woman remarked, “Well, you know my house is so complete I really don’t need anything, but I do like that antique chair in the library.” Eileen and Bonnie promptly doubled the chair’s price tag and were delighted to see the snob pay it.

In November the family moved in with Grandmother Sebring in Sebring, her big house already filled with impoverished relatives. What was to be a brief stay before going west was delayed for months. Grandmother was having heart attacks. Eileen’s daughter Patricia (who was to be Chris Crain’s mother) had surgery which failed to cure a puzzling illness. (In California, Patty asked to be taken to a healing service of evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson after hearing her on the radio. Mrs. McPherson prayed and anointed her with oil. Patty told her mother she was healed, and indeed her illness never returned.)

More treasured possessions were sold to pay bills. With the return of warm weather, the Taylor group relocated to the country air of a cabin Pearl owned on the Sebring camp meeting grounds. Pearl’s prayers prompted her to read Psalms 68:13: “Though ye have lien among the pots, ye shall be as the wings of a dove. . .’ She told the others, “I don’t know where we are going to get the money for our trip, but since the Lord wants us to go, He will provide the way.” That same day a woman came to the cottage with an offer to buy it, the amount sufficient to fund their trip. That was one of several instances Eileen recorded in which answers to prayer appeared to guide their decisions and provide the means.

Tears streamed down Grandmother Sebring’s face as they left for California by car pulling an overloaded trailer. She called, “Goodbye, goodbye, I’ll never see you again.” (Eileen)

A chicken coop for a pottery

Many flat tires and long, dusty roads across America later, though thrilled to see Homer, John and Uncle Ray after a whole year, the travelers were shocked at Homer’s appearance. He had a painful skin cancer on his face and had not seen a doctor because of the expense.

They found a house, and with the car they could sightsee and look for jobs. Everybody did what they could for money. Eileen and Bonnie worked at a series of sales jobs but the shops always went under. Homer and Eileen worked for a real estate agent who stiffed them on commissions. Homer sold letters from President McKinley. Pearl and Bonnie knitted, earning 75 cents per sweater. When Eileen received money from a small property sale back home, Homer and John used it to set up a little pottery retail shop on Sunset Blvd. It failed.

Eileen enrolled in evening typing classes, realizing “we weren’t educated to do much of anything.”

But they did know how to make pottery.

One night as Pearl said her prayers, she began laughing and weeping, saying The Lord “wanted us to start our own little pottery where we could all work together.” (Eileen) When funds arrived unexpectedly from the sale of a Florida property, they went looking for a building.

Homer and John saw four large buildings in Burbank that turned out to be empty chicken coops. The owner agreed to rent one for $10 a month. It was 24 by 80 feet. To their delight they found a good cement floor under layers of chicken poop and feathers.

A nearby pottery agreed to sell glaze and fire their ware. Clay was mixed by hand in a large barrel. Trim knives came from the five and dime. A plaster worker was hired to make six molds from a glass vase, then added more molds. Old lumber was turned into shelves and workbenches.

The world did not owe them a living

Money to build a single bottle kiln to fire their own ware came via a minister the Taylors had known back home who was now in Los Angeles. A woman in his congregation asked his guidance in investing money. She became a partner in KTK CA.

It took 300 pieces and “hard, hard work” to fill that kiln, Eileen said. The first firing was overheated, a terrible disappointment, every piece a ghastly yellow gray. Hiring a competent fireman for the second try produced long rows of saleable ware in lovely pastel shades and hope was renewed.

Money always seemed to come from friends when most needed. A doctor friend asked one day why the kiln was filled with green ware but sitting idle. The answer was an unpaid $57 gas bill. He had just received a check for $57, considered that a sign, and handed it to them as a loan.

In 1941, Homer wrote to his former attorney, William H. Vodrey, asking if he could arrange a $4,000 loan to purchase the land and buildings of their pottery. Vodrey instead tapped wells of East Liverpool wealth and friendship which had survived The Depression. Vodrey, Fred B. Lawrence, Marcus Aaron, H.H. Harker, Edwin M. Knowles, and C.A. Smith chipped in, sending the money as a gift, not a loan, to Homer and Pearl.

In his solicitation letter to Aaron, Vodrey described the family’s situation, saying a small house, 20 by 20, was built on the site, with “as many Taylors as can find room living in the house” and using toilet facilities in the factory. “Homer has his room in the factory. . .” He and Pearl “do the ordinary labor required of a small pottery. . . Their courage seems marvelous and demands our admiration . . . Homer and Pearl are not discouraged, they are not critical and they do not claim the world owes to them a living.”

When the money came Homer had not long to live.

In the end, success in pottery and life

A snapshot of KTK CA pottery’s workforce in 1942 showed a dozen people standing in front of the old chicken coop. They had a gas tunnel kiln now, funded from an investor’s personal loan sealed by a handshake.

The “hand-made” ware they developed was a creation of necessity. The technique allowed them to multiply their stock offerings without the expense of new molds. Taking basic mold shapes, they bent, twisted, sliced and decorated the ware while it was green and pliable, affixing ribbons, bows, flowers and twisted handles in a way never done before. The beautiful results are highly distinctive and prized by collectors of California art pottery of the period. A “KTK -CA” logo and model number identification were often knifed into the base instead of a backstamp in early ware, sometimes with the initials of the individual who made it. Chris Crain can often identify the maker by handwriting.

While still working at the pottery, Pearl nursed both her sister Annie Sebring McMurphy and her husband Homer through their terminal illnesses. Annie died in 1942.

“Homer’s face cancer grew worse and the pain so excruciating that one evening he wept and asked Pearl If she would pray and ask God to take him in his sleep,” Eileen wrote.

Homer went into a coma. Eileen was present when, she said, “the brightest light I have ever seen shown on my father’s face, he opened his blue eyes, looked up and smiled” as he died. It was April 16, 1943.

As family members moved forward in their lives, Homer and Pearl’s son John Oliver eventually became sole owner of their little pottery. His effort to move into dinnerware failed, and KTK California ended in 1948. Pearl lived with daughter Bonnie as her health declined in the late 1940s. She died Dec. 8, 1948. John died in 1958 at age 51.

Bonnie Taylor had met and wed Lee Wollard, whose name is familiar to collectors of California art ware. The Lee Wollard line of intricately detailed ceramic figurines lasted into the 60s. Lee introduced Eileen to her second husband, E.O. “Dubby” Davidson. They labored with Pearl in the last years of the KTK CA pottery and had their own short-lived “Dubby” line of fanciful ware.

Patricia, daughter of Eileen and Harold McNutt, married John R. Crain. Their son Chris is author of the “Riches to Rags” book. Eileen died Sept. 7, 1990, at age 88.